TOGETHER WITH

Humans built the most powerful communication network in history, and then designed it to spy on us.

This wasn't an accident, and it wasn't due to some technical oversight. No, it was because we chose an economic model that treats personal data as the most abundant and cheapest fuel source available in cyberspace.

Twenty-five years later, we're all still paying the price.

TL;DR

Ad-supported business models made surveillance the default, not privacy.

Loyalty programs are a prime example of how “free” services extract payment through attention, time, and personal data.

Privacy regulations have failed to change economic incentives, and companies continue to profit more from harvesting data than protecting it.

AI has exponentially increased the stakes—your data now trains systems that shape your future and enables social engineering on a massive scale.

Individual privacy erosion has become a significant corporate cyber risk that many companies are not accounting for.

We chose surveillance by default, but we can still opt for privacy by design.

An entire industry now profits from cleaning up a mess that never should have existed.

What is the Real Cost of "Free"?

What's the "value" of something free, and what is the cost?

Let's break down what the "cost" of free means when it comes to data privacy. But first, we'll need to borrow some economic terms to better understand this space:

Free Goods - Goods that are not scarce, are available in unlimited quantities, and whose consumption by one person doesn't reduce their availability to others.

Opportunity Cost - The value of the best alternative that you decided not to choose when you make a decision.

Zero-Price Effect - People often exhibit a psychological bias toward things that are "free." They tend to overvalue goods or services offered at zero cost, even when the "free" option is not as good as paid alternatives.

Hidden Costs - This idea that even when something looks "free," there might be hidden costs like time, attention, or data that someone has to "pay." When something appears to be free, you're likely paying with a different currency.

Zero-Sum Game - The economic theory of competition where one side can only win at the other side's loss. You're either a zero or a one.

Here's a real-world example of how this works.

Vanderbilt University's recent paper, The Loyalty Trap, dissects how rewards programs have become surveillance infrastructure masquerading as customer perks. The numbers tell the story:

McDonald's: 150 million loyalty users whose orders, locations, and app interactions are tracked.

Nordstrom: 13 million members whose purchasing patterns are extensively profiled.

Grubhub: 25 million monthly users whose eating habits are monitored and monetized.

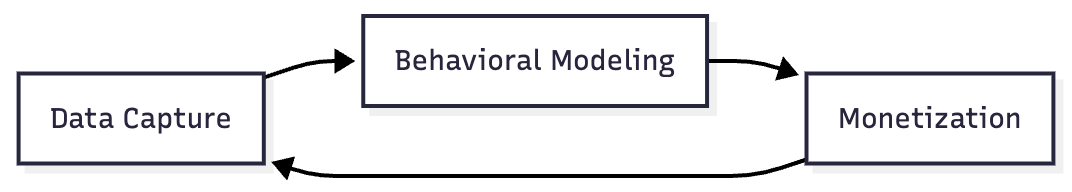

It’s all done via a shareholder-value-increasing, three-stage extraction process:

Infinite Money Glitch

You get a free coffee after ten purchases at McDonald’s. They get a perpetual profile of your behavior that they can monetize indefinitely. The zero-price effect and hidden costs are playing out in real-time, millions of times per day.

Now apply these concepts to your personal data as a whole. See now why data privacy has been treated as an afterthought?

An entire industry profits from creating a problem that never should have existed, and it has remained mostly untouched for the past few decades. Only in recent years have we begun to see changes, and now a new group of businesses is addressing a problem that should never have existed.

The economic incentives, trade-offs, and rewards were never aligned to protect your personal data. "There's no such thing as a free lunch," as they say.

We could have done this differently, but we didn't realize we were playing a zero-sum game and didn't understand the trade-offs happening to us.

The Origin of the Privacy Trade-Off

Advertising was the Internet's original sin and trade-off we didn't see coming.

A few banner ads were placed on various websites we frequently visited. Maybe we'd see an ad for something we wanted to buy, or maybe we would just ignore it. Either way, our collective knowledge of what was available to us on the web grew with each new site we visited. Shopping online offered more selection than any local store could, and connected us with people and places we would never have interacted with otherwise.

Social media was the same way. It offered more connection opportunities than offline circles and allowed you to stay in touch with people whose lives may have gone in different directions from yours (also, it’s great at helping you remember random people’s birthdays).

But once businesses realized that ad-supported business models worked, they became the default operating mode. The business of user tracking to serve better, more relevant, and more timely ads was born.

We all accepted it because we had no idea what we were giving up. Even if we had known at the time, the value would have probably seemed worth it. And to be fair, neither side was truly aware of the trade-offs or how they would evolve, but the business side of the equation caught on much faster than the consumer side.

As I've written before in Understanding Digital Footprint Management, data collection went from passive analytics to aggressive aggregation in a hurry.

Scraping, mining, and reselling information you didn't know was being collected on you, and that you had no idea businesses would find valuable. All the while, the data aggregation universe was happily scraping, harvesting, and monetizing your life, turning personal details into profit.

If you want an example of just how far this has gone, consider the Gravy Analytics breach. This location data giant was breached, exposing years of granular movement data sold to law enforcement, advertisers, and who knows who else.

As Matt Johansen said in his piece on the Gravy Analytics piece:

"This is the result of an advertising industry gone mad. The desire to serve ads based on extreme context has led to our every move being tracked, not just across the web with cookies but in the physical world since we all carry a super-powered tracking device in our pockets."

By the time this breach came around, the genie had long been out of the bottle, and there was no chance of getting it back in.

The Industry That Shouldn't Exist

Early security professionals sounded alarms on data misuse, surveillance capitalism, and personal exposure.

But privacy wasn't "sexy," actionable, or monetizable in those days. Even within security, privacy was often viewed as a niche or legal-adjacent concern, rather than central to threat modeling or risk reduction for individuals and businesses alike.

If you need proof of systemic failure, look at the booming market for Digital Footprint Management services. Platforms like DeleteMe and others are becoming household names, but these companies are not the villains of the story. They're more like the emergency response crew at a pile-up on a section of the interstate, notoriously known for its frequent crashes.

In my analysis of the Digital Footprint Management market, I outlined how this sector emerged to help individuals and businesses claw back some measure of control:

Data Broker Opt-Outs: Submitting takedown requests to dozens or hundreds of people-search and marketing aggregation sites.

Search Engine De-Indexing: Hiding sensitive URLs from search engine results.

Continuous Monitoring: Because removing data once is never enough, since it repopulates like weeds.

Dark Web Monitoring: Trying to catch the inevitable leak after the brokers resell your details to anyone.

These services are inherently good. But the fact that they're necessary at all is an indictment of the entire system.

When companies collect and resell personal data and regulators fail to rein them in, the burden falls on individuals to clean up a mess they never knowingly created. Data privacy isn't just about protecting data. It's about what we've lost by building everything on surveillance by default.

Some examples of what’s been lost to the surveillance economy:

Trust in technology: People are increasingly wary of the tools that promised to empower them.

Freedom of expression: Fear of being tracked or doxxed chills open participation.

Resilience against abuse: A Lawfare piece on people-search brokers shows, stalkers, harassers, and even murderers use purchased data to find and harm victims.

“But wait!” you say. “What about all of those privacy regulations?”

The Illusion of Control from Regulators

Both the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in the European Union and the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) in the United States were designed to shift the economic incentives around data protection.

These are just the big ones, of course, and don’t even come close to describing the complexity on the regulatory side. The IAPP’s US State Privacy Legislation Tracker is the best resource I've seen for tracking what's going on in the United States.

The core idea around privacy regulation was to make noncompliance so costly that organizations would find it rational to invest in protecting personal data. The underlying premise was that, if the penalty for misuse is high enough, companies will invest in necessary consumer protection measures and curb their insatiable hunger for end-user data at all costs.

Both laws are grounded in the idea that economic incentives drive organizational behavior (and I believe that is true). By making the cost of non-compliance steep and cumbersome enough, through fines and lawsuits, and greater than the cost of compliance, GDPR and CCPA aimed to encourage proactive investment in privacy and data security.

Capitalism has entered the chat…

GDPR also introduced an unintended side effect that we couldn't have predicted: self-exclusion from innovation.

The saga of Meta’s Llama model, a family of large language models (LLMs) designed to be open and accessible, and the European Union (EU) regulators, is a case in point:

Meta pulled its multimodal AI release in Europe, citing regulatory uncertainty.

The Irish DPC, in coordination with other EU regulators, has spent over a year negotiating whether using public posts for AI training is compliant.

Meanwhile, Europeans are left watching advanced tools roll out elsewhere.

Consider the cookie consent pop-ups that have blanketed the web (there’s even one on this site). Consent banners haven't meaningfully improved privacy by any measure, but they’ve almost certainly ruined the web browsing experience by the only measure that matters (perception).

They've also mostly trained people to click "Accept All" without thinking. Brilliant!

Me yelling at you for accepting cookies

But as time has passed, the limitations of privacy regulations have become clear. Enforcement is uneven. Compliance is often a superficial checkbox exercise. Fines, no matter how big they sound in headlines, are a rounding error for Big Tech. Some even get easily pushed back.

For a recent example of regulatory backsliding, consider how the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau quietly withdrew its proposed rule to limit the sales of sensitive personal information by data brokers. The agency reversed course just weeks after a new administration took office, declaring the rule no longer "necessary or appropriate."

This reversal demonstrates how quickly privacy protections can be undone by changing political winds, while individuals and businesses are left holding the bag.

The underlying goals of regulation were at least well-intentioned, however. Protecting minors and preserving individual dignity are good things and should be the default standard.

But there's a difference between a business write-down and enforcement that reshapes incentives.

Since GDPR came into effect in May 2018, total fines have reached approximately €5.88 billion (USD $6.17 billion) across all of Europe. While this sounds substantial, GDPR fines in 2024 totaled €1.2 billion, a 33% decrease from the € 1.8 billion in 2023.

For context, Meta alone generated $48.3 billion in revenue in 2024. A few hundred million in fines is simply the cost of doing business for Big Tech.

And, right now? The math still favors harvesting data over protecting it.

Reframing the Problem

Of course, it's tempting to see this as a purely technological problem.

If only we had better encryption, more effective governance and compliance tools, or greater societal awareness. If only people were more responsible with their own data!

But at its core, data privacy is a problem of economic incentives (as are many cybersecurity problems).

The business incentive to collect and exploit data is massive! The incentive to protect data is… well, not as great.

Until the economic equation changes, that is, until privacy is profitable and surveillance is expensive, nothing will fundamentally improve.

This is why I often come back to the phrase: the opportunity cost of data privacy. Every time we accept the convenience of free, frictionless experiences without questioning the trade, we're paying that cost. This is true from a personal standpoint, and it is becoming increasingly true from a business standpoint as well.

When Personal Becomes Corporate

Things are starting to turn, however.

People and businesses now have tools, awareness, and growing legal leverage to take action. Solutions exist not just to remove your data, but to reframe how and where it's used.

The value curve of privacy is shifting from blocker to differentiator. There's now a return on privacy (see what I did there?), and the market is beginning to recognize it.

Digital Footprint Management services are becoming more mainstream for a reason, and that's because they work. This isn't a luxury anymore, or only for tinfoil hat-wearing people. If you're in any profession where your identity as an executive, journalist, lawyer, activist, or just someone who values their safety is valuable, these are useful tools.

This line of thinking requires an economic reframing, one that aligns privacy protection as another form of insurance. And this is where individual privacy extends beyond just you and your sphere of influence.

Individual privacy loss doesn't stop with individuals, it has been blended and extended into the corporate realm.

Every employee who's been digitally profiled for the last 15 years represents a corporate vulnerability that nobody's accounting for in their threat models. Every executive whose home address is $0.25 on a data broker site is a social engineering target waiting to be exploited. Every developer whose GitHub contributions, LinkedIn history, and Twitter opinions can be scraped and analyzed by AI in seconds is a potential attack vector.

The Data Broker Infrastructure

From an attacker's perspective, employee exposure == attack surface. Data brokers are a discount reconnaissance infrastructure.

Every detail about your employees' lives, their relatives, their homes, their habits, and their social connections is reconnaissance data for social engineering, doxxing, or stalking.

A few years ago, this level of reconnaissance required human analysts and a risk-versus-reward calculation. Today, an attacker with an LLM ingests those data broker profiles, does additional OSINT on any other information about you, and gets the perfect context. For less than the cost of a nice dinner (or a pint of Guinness 🍺 ), an attacker can purchase comprehensive profiles of your entire executive team.

This brings to mind another economic term of asymmetric information. It’s where one party in a transaction has more or better information than the other, which can lead to advantages and leverage over the other party.

This is an externality that has not yet been fully priced in on the data privacy front. Companies that invest in employee privacy protection aren't just reducing their own risk, they're changing the economic equation for attackers.

Reducing the reconnaissance data available to attackers may make social engineering harder to execute at scale, though measuring the downstream effects on individual security controls is inherently difficult without critical industry mass. Collective defense only shifts attacker economics when enough organizations participate. We're still building from the ground up.

Final Thoughts

Smart companies are starting to figure this out. Enterprise Digital Footprint Management programs are emerging, not just as HR benefits, but as additional security controls. Executive protection services that used to focus on physical security now spend more time on digital exposure reduction than on bodyguard services.

We built an economy where personal data was free to harvest and expensive to protect.

Markets always respond to money and incentives (even the bad kind of markets). When enough organizations make reconnaissance expensive again, the entire attack model becomes less viable. Changing the cost structure changes the behavior.

The bad news is that we could have done this differently from the start. The good news is that we still can.